Terraforming: Can you really Nuke the Mars?

- theexploreroffice

- Aug 7, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Aug 9, 2025

In ancient Rome and Greece, the mythology of Mars and Ares, the gods of war, is quite famous. The Roman god Mars was considered a fearsome and mature warrior, often depicted with a long beard and clad in armor. His Greek counterpart, Ares, was seen as a much younger and more impulsive figure. Ares was often accompanied by two close companions: Phobos and Deimos.

Phobos (meaning fear) and Deimos (terror) had one job — to spread enough panic and dread among the enemies that they would flee, leaving the farmers and innocent people unharmed.

The Roman god of war, Mars, was also believed to fight not for chaos, but to protect and uphold justice, battling evil for the good of the people.

According to Roman mythology, Mars was born to King Jupiter and Queen Juno, the king and queen of the gods.

The ancient mythologies of Rome and Greece have carried forward through the ages. The planet Mars has been observed since ancient times, with early records found in Egyptian, Chinese, and Roman literature. Its distinct red color naturally drew attention, and many ancient cultures associated it with blood, fear, and power — fitting symbols for a god of war.

When the two moons of Mars were discovered by Asaph Hall in 1877, they were named Phobos and Deimos, in honor of the mythological companions of Ares. It was a poetic choice — drawing from ancient mythology to name the modern scientific discoveries orbiting the red planet.

THE SIBLINGS

Mars, the fourth planet from the Sun, is approximately 227.9 million kilometers away from it. On average, it lies about 225 million kilometers from Earth, depending on their positions in orbit.

Mars is truly like a younger sibling to Earth—you can’t help but notice the many similarities between the two.

IS THERE A LIFE ON MARS?

In 1877, Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli looked at Mars through his powerful telescope and observed mysterious lines crisscrossing the planet’s surface. In Italian, he described them as “canali,” meaning channels or grooves. However, when translated into English, the word became “canals,” a term strongly associated with artificial waterways, like the Panama Canal or Suez Canal.

This simple translation sparked a wave of speculation and excitement. If there were canals on Mars, people reasoned, there must have been water. And if there was water, perhaps there had been intelligent life capable of building such structures! Schiaparelli’s maps fueled the first major public interest in the idea that life might exist on another planet.

About 20 years later, in 1896, American astronomer Percival Lowell became fascinated by Mars. He spent two decades observing the Red Planet through his own telescope and claimed to have seen and recorded around 437 canals. Over the years, Lowell created detailed maps of these Martian canals, firmly believing they were built by an advanced alien civilization trying to distribute water from the polar caps to dry regions.

Though later science disproved the idea of artificial canals, these early observations by Schiaparelli and Lowell ignited global curiosity and marked the beginning of serious thinking about life beyond Earth.

MISSION MARS

Once there was growing curiosity in the 20th century about the possibility of life on Mars. Decades after the first Moon landing in 1969 by Neil Armstrong aboard Apollo 11, a new race began—not just to explore space but to reach the Planet Mars!

During the 1960s and 70s, NASA launched a series of flybys, orbiters, and even the first landing missions to Mars. (See image above of Viking -1 Mission by NASA).

Once, there was growing curiosity in the 20th century about the possibility of life on Mars. Decades after the first Moon landing in 1969 by Neil Armstrong aboard Apollo 11, a new race began—not just to explore space, but to reach Mars.

The Mariner series of flybys, launched in 1964 and 1969, were the first to capture close-up images of the Martian surface. These images revealed a cratered landscape, much like our Moon, and showed that Mars had a thin atmosphere made mostly of carbon dioxide (CO₂).

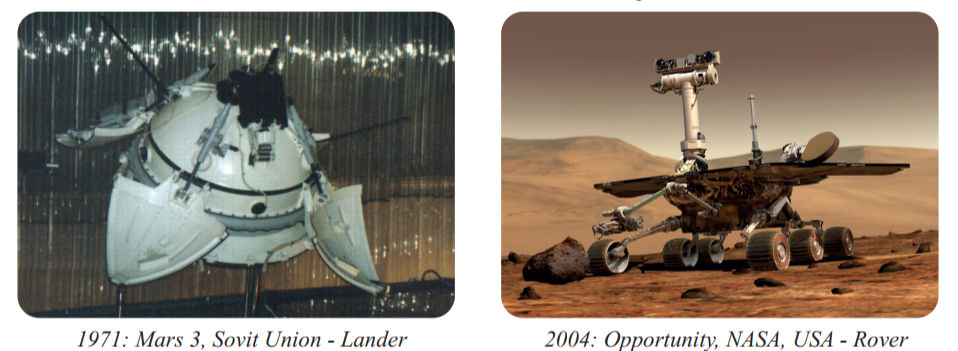

In 1971, the Soviet Union sent the Mars 2 and Mars 3 missions. Although Mars 3 successfully landed on the surface, it failed just 20 seconds after touchdown. Still, Soviet scientists managed to receive about 60 detailed photographs of the Martian surface—an impressive achievement at the time.

The real breakthrough came with NASA’s Mariner 9, also in 1971. It became the first spacecraft to orbit another planet and began mapping the surface of Mars from space. Thanks to Mariner 9, we discovered Valles Marineris, an enormous canyon system larger than Earth’s Grand Canyon.

Years later, NASA’s Pathfinder mission, along with the Sojourner rover, made history by exploring the Martian surface for 85 days. This was the first time scientists directly analyzed Martian rocks, opening a whole new chapter in planetary science.

Fast forward to 2004, NASA launched the famous twin rovers—Spirit and Opportunity. Originally expected to last just 90 days, Opportunity stunned the world by operating until 2018. It became the first rover to confirm the presence of ancient water on Mars—solid proof that Mars may have once supported conditions suitable for life.

All of this curiosity traces back to Schiaparelli’s 1877 observation of so-called “canals” on Mars. That single moment planted the idea that water might exist on the Red Planet. And now, with everything we’ve discovered so far, the question becomes: what’s next?

Of course, we explore the possibility (or should I say... “Opportunity”? ) of future human life on Mars. NASA’s Curiosity rover, currently exploring Gale Crater, is paving the way by studying Mars’s habitability, one rock sample at a time.

And the journey doesn’t stop there. In recent years, new players have entered the scene—China’s Tianwen-1 mission successfully deployed its Zhurong rover, while the United Arab Emirates’ Hope orbiter began studying Martian weather patterns. Most impressively, NASA’s Perseverance rover and its tiny companion, the Ingenuity helicopter, are now pushing boundaries even further. Perseverance is not only analyzing rocks for signs of ancient microbial life, but it’s also collecting samples that may one day be returned to Earth.

Earlier, we explored the many similarities between our planet Earth and its younger sibling, Mars, and it might make us think: “All we have to do is hop into a rocket and move there!”

Alas! Such is not the case.

Mars is inhospitable—let alone inhabitable.

Here are a few reasons why:

The atmosphere of Mars is made up of 95% carbon dioxide, with just 0.15% oxygen—the very gas we need to breathe and stay alive.

Mars also has extremely thin air.

While on Earth, we experience about 14.7 pounds per square inch (psi) of pressure on our skin, Mars has barely 0.087 psi. That’s less than 1% of Earth’s atmospheric pressure. This thin atmosphere is not just bad news—it’s instantly deadly. Without a pressurized suit, a human body would literally explode outward, because of the internal pressure within us.

Mars is also, on average, 225 million kilometers away from Earth. That great distance from the Sun means we get only about half the sunlight on Mars compared to Earth.

And with that lack of sunlight comes bitter cold. Temperatures on Mars range from -88°C to about 12°C, and that’s on a good day. The only relatively warmer zone is near the Martian equator—which, coincidentally, is where NASA’s Curiosity Rover is currently exploring.

The climate is so harsh that the poles are permanently frozen, and in the Martian winter, temperatures there can plunge to a bone-chilling -140°C. And don’t even think about sunbathing! Mars has no strong atmosphere to protect you from the Sun’s ultraviolet radiation.

So, in such an inhospitable world, one must ask:

Is there truly any chance for humans to settle down on Mars?

Every story needs a hero. And in our story, that hero is called Frederick Turner. Frederick Turner is a scientist who, proposed a bold and outrageous idea to make Mars habitable. The method is known as terraforming.

Now believe me when I say this: Frederick Turner is a hero—not a villain—even though his idea might sound like something straight out of a comic book supervillain’s playbook. His proposal?

Drop nuclear bombs on Mars!

Yes, you read that right. We know that Mars is home to many volcanoes. In fact, the largest volcano in our entire Solar System is located there. It’s called Olympus Mons. This gigantic volcano stands at a towering 21,900 meters (71,682 feet) tall! Though it hasn’t erupted in millions of years, Turner’s idea was to reactivate these volcanoes—by dropping nuclear bombs into them. Sounds crazy? Sure. But there’s a method to the madness.

Why bomb volcanoes?

The idea is that by activating these volcanoes, we can release heat and carbon dioxide (CO₂) into the atmosphere. Here’s what that would do:

Mars is freezing, with temperatures ranging from -88°C to 12°C—hardly ideal for humans. Volcanoes spitting out lava and heat would help warm up the planet.

The released CO₂ would thicken the Martian atmosphere. It would trap heat from the Sun, just like a greenhouse on Earth. That means more warmth stays on Mars instead of bouncing back into space.

Thicker air = higher air pressure. That solves one of our biggest problems: right now, Mars’s atmosphere is so thin that humans would explode from internal pressure without a suit. More CO₂ means more survivable air pressure.

With higher temperatures, the ice caps on Mars could start melting. But if that doesn’t happen quickly enough, Turner (and later Elon Musk) proposed placing giant mirrors in orbit to reflect more sunlight onto the ice caps, speeding up the melt.

Once we get liquid water from the melting ice, we can introduce algae into the Martian lakes and oceans. Why? Because algae on Earth produce about 50–80% of the world’s oxygen. If we do the same on Mars, we can start turning CO₂ into O₂—oxygen, the stuff of life.

Comments